Blog

Chandra Talpade Mohanty on pedagogies of dissent

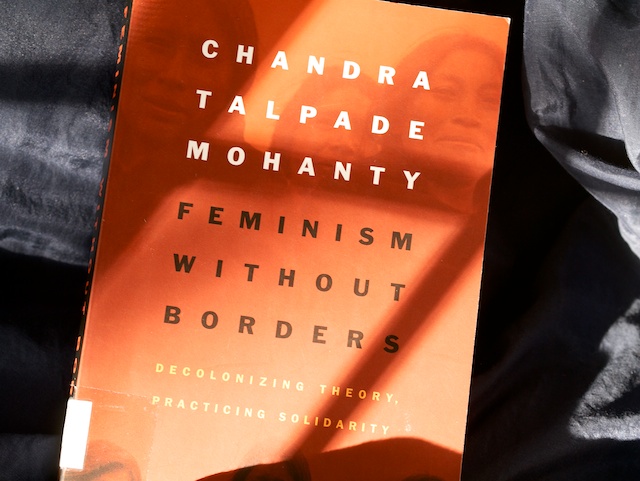

In her 2003 book, Feminism without borders, Chandra Talpade Mohanty draws links between daily life, collective action and alternative pedagogies.

In her eighth chapter, titled Race, Multiculturalism and the Pedagogies of Dissent, Mohanty writes:

How do we construct oppositional pedagogies of gender and race? Teaching about histories of sexism, racism, imperialism, and homophobia potentially poses very fundamental challenges to the academy and its traditional production of knowledge, since it has often situated Third World peoples as populations whose histories and experiences are deviant, marginal, or inessential to the acquisition of knowledge. And this has happened systematically in our disciplines as well as in our pedagogies. Thus the task at hand is to decolonize our disciplinary and pedagogical practices. The crucial question is how we teach about the West and its others so that education becomes the practice of liberation. This question becomes all the more important in the context of the significance of education as a means of liberation and advancement for Third World and postcolonial peoples and their/our historical belief in education as a crucial form of resistance to the colonization of hearts and minds. As a number of educators have argued, however, decolonizing educational practices requires transformations at a number of levels, both within and outside the academy. Curricular and pedagogical transformation has to be accompanied by a broad-based transformation of the culture of the academy, as well as by radical shifts in the relation of the academy to other state and civil institutions. In addition, decolonizing pedagogical practices requires taking seriously the relation between knowledge and learning, on the one hand, and student and teacher experience, on the other. In fact, the theorization and politicization of experience is imperative if pedagogical practices are to focus on more than the mere management, systematization, and consumption of disciplinary knowledge.

With this in mind, she goes on to say:

Teaching practices must also combat the pressures of professionalization, normalization, and standardization, the very pressures or expectations that implicitly aim to manage and discipline pedagogies so that teacher behaviors are predictable (and perhaps controllable) across the board.

Later in the chapter, she quotes Esla Barkley Brown on her experience with teaching African-American women's history:

How do our students overcome years of notions of what is normative? While trying to think about these issues in my teaching, I have come to understand that this is not merely an intellectual process. It is not merely a question of whether or not we have learned to analyze in particular kinds of ways, or whether people are able to intellectualize about a variety of experiences. It is also about coming to believe in the possibility of a variety of experiences, a variety of ways of understanding the world, a variety of frameworks of operation, without imposing consciously or unconsciously a notion of the norm.

A lot to think about!

(Courtesy astripedarmchair.wordpress.com)

(Courtesy astripedarmchair.wordpress.com)

- Log in to post comments