Accession card

Description

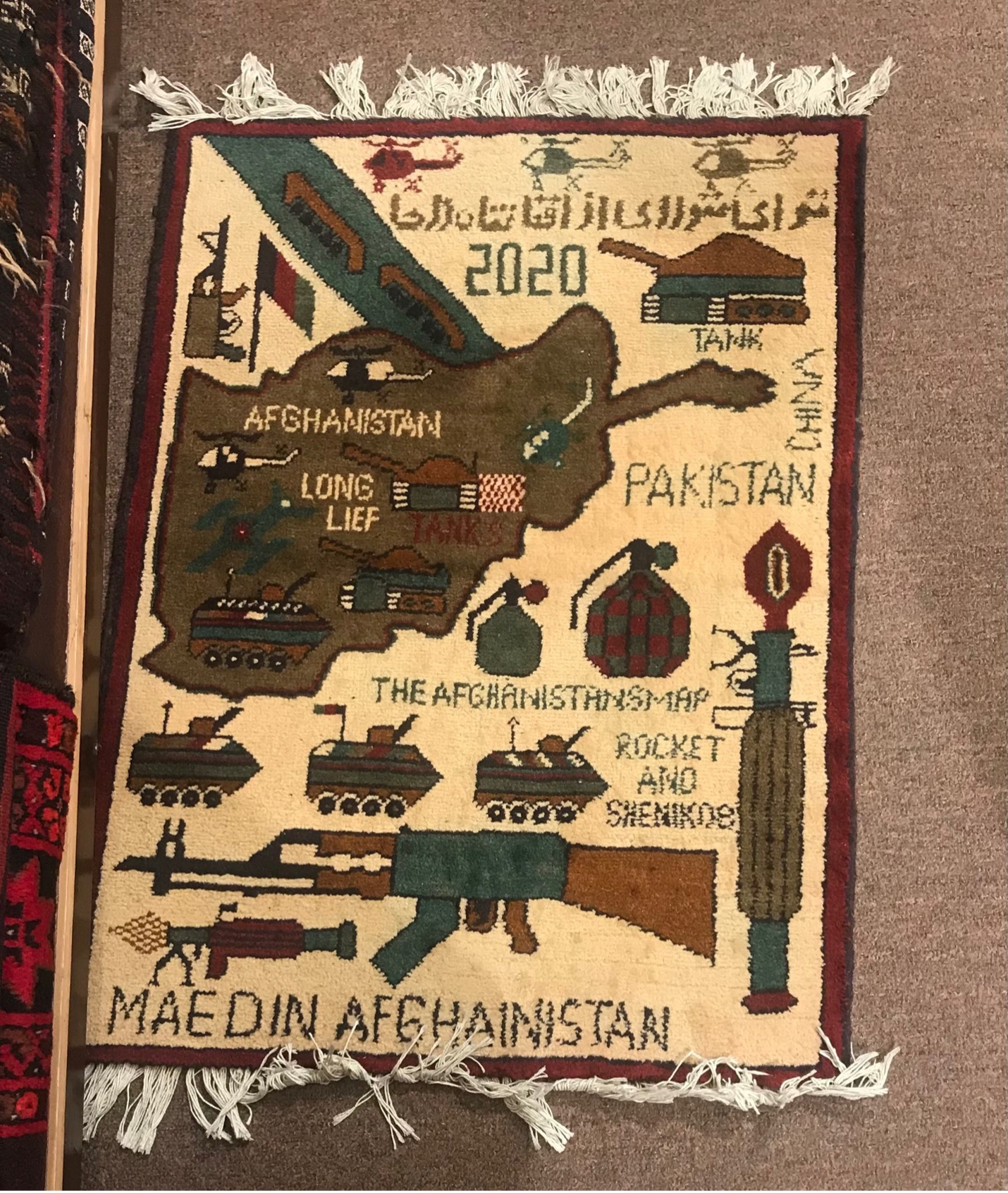

In the winter of 2021 while visiting family in Pakistan, I was searching the carpet stores of Islamabad for an affordable rug to take back to Toronto. Islamabad, with the highest number of foreign diplomats in Pakistan, is full of art and craft stores in central locations which cater mainly to non-Pakistanis. As compared to stores which target locals, these craft stores have a well-curated collection of ‘authentic-looking’ craft that appeal more to Western palates. It was in one of these spaces that I chanced across a small woven rug, around 2 x 3 feet, unlike anything I had ever come across before. On a cream-colored background, was the map of Afghanistan sprinkled with images of tanks, helicopters, guns, grenades, and rockets. Across the bottom, letters spelled ‘MAED IN AFGHAINISTAN’ and on the sides of the map of Afghanistan were labels of ‘Pakistan’, ‘China’, the year ‘2020’ and words such as ‘Rocket’ ‘Tank’ etc. (refer to the image). This rug startled me, and I immediately took a picture, determined to research more later. In my mind, I was convinced that this was a one-of-a-kind rug-- something that hardly anyone could have chanced upon.

However, as the collector Enrico Mascelloni aptly states, “based on a general rule in Central Asian bazaars, when one buys something that seems unusual, they are bound to find thousands more like it”. Though my experience was not in a ‘Central Asian’ bazaar, a quick Google search returned thousands of images of ‘Afghan War Rugs’ with several Etsy stores and eBay sellers dedicated to selling Afghan rugs within North America. Not only is there a dedicated website warrug.com, but there is a dedicated book by Enrico Mascelloni, several news articles, coverage of several exhibitions on Afghan War Rugs, in the US, Germany, Australia and Canada. Despite the seemingly large interest in Afghan War Rugs, accounts on who makes these rugs, why they are so popular and what even propelled these designs in the first place, are conflicting and unsatisfactory. Some scholars admit that to even call these rugs ‘Afghan’ is perhaps misleading as many of these are now made by refugees in Pakistan—mainly Peshawar. Despite ‘exciting’ accounts of ‘oriental’ marketplaces and stories shared by dealers, it is often the case that the dealer deals not with the weaver but through a chain of other dealers. The weaver is barely represented in this operation and is reified to the extent that they become a ‘myth’ of sorts. Works by art historians and collectors have largely been based on lore without any access to, or even attempt to collect, independent ethnographic data. Hence, there are limits to what can be known and the limits are not recognized or (even admitted to) by ‘experts’. However, though admittedly it is difficult to unpack the ‘origins’ of a thing, what remains to be understood is why are Afghan War Rugs wrapped up in narratives of romanticized trauma and marketed for their ‘authenticity’?

At a talk at the In-Situ Graduate School Workshop in Leiden, it was argued that Afghan war carpets are representative of the 'trauma' of Afghans, hence their appeal. This claim and the insistence that their designs represent a true experience of war seems voyeuristic desire to peer into the emotional experience of Afghan civilians— a clear reflection of the United States preoccupancy with the Afghan ‘victims’ of the Soviet Union and later the Taliban. However, to assume that weavers would put depict their own experiences of war into display for the world is too unsophisticated a view that reflects 'Western' ideas of what Afghan victims wish to communicate. To consume these rugs for their representations of the ‘trauma’ of war is to give into the fetish of souvenirs—in this case ‘war’ souvenirs. How then do we approach the study of Afghan War Rugs, when information is limited and unreliable and access restricted?

Reference:

Mascelloni, Enrico. War Rugs: The Nightmare of Modernism. Skira, 2009.

Code

Date

Title

Medium

- Image